Before COVID-19, the literature courses I taught tended to have a similar structure. We might start with a low-stakes check-in quiz or a bit of ungraded free-writing, maybe building off of a comment or two from the live-tweeting a couple of designated readers had done the day before using a class hashtag. We’d compare notes, or quickly grade the quiz together. And then I’d ask the question many therapists use to open a session: where do you want to begin today?

Lecturing wasn’t really a “thing” I did — but that’s not to say I didn’t plan each lesson. The challenge of open-ended discussion involves balancing the facilitator’s priorities with learners’ interests and curiosity. That means anticipating what kind of background might be necessary to answer certain questions and making space for a little informative sidebar (NEVER for more than 5 or 6 minutes!) before diving back into the questions and answers and “what do you think”-ing that makes teaching in the humanities distinct.

But COVID-19 means that face-to-face instruction isn’t going to happen as usual for a while. And given the documented reality of Zoom fatigue, instructors can’t simply hope to recreate their usual discussion-based magic mediated by a screen. Instead, everyone teaching needs to think carefully about what kind of material should happen synchronously, via Zoom, and what can happen asynchronously, on the student’s own time.

This kind of calculus isn’t news to anyone who has experimented with flipping the classroom. But it does mean getting over lecture-phobia and figuring out how to make the asynchronous learning materials that you create interactive, fun, and (most importantly!) not overwhelming for the self-guided learner.

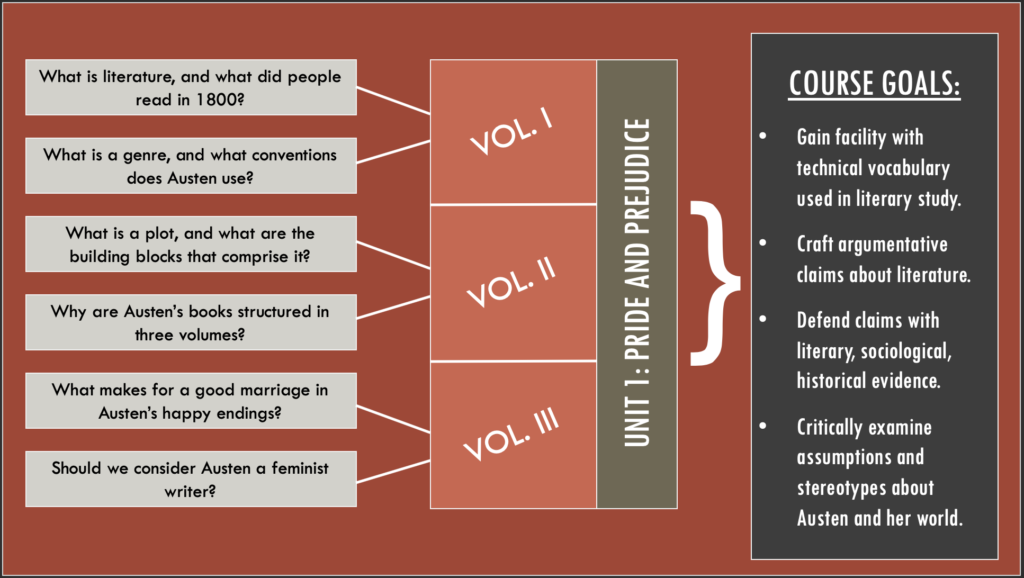

I developed this module for a course I teach on Jane Austen, to correspond with the second day of discussing Pride and Prejudice, the first novel we read. The course is an introductory-level English class in which we read all six of Austen’s novels, plus some shorter fiction, poetry, and essays for context. As the first unit in the course, Pride and Prejudice is supposed to accomplish a few goals overall.

First, it reintroduces (or perhaps introduces!) the technical and formal vocabulary of literary analysis. One of the outcomes of the whole class should be gaining facility with using words like “exposition,” “genre convention,” and “third-person perspective,” but not every student has the same exposure to that language at the outset.

Second, it introduces Jane Austen, a person about whom many people know nothing at all! That’s not to say they don’t have some preconceived notions about who she was and what life was like in England around 1800. But since we’ll spend 14 weeks with her, we need to start doing some critical thinking about those, asking questions like these and learning some history.

Finally, it models what claims about and evidence from literary works look like in anticipation of the first major assignment for the course, a simple position paper: “If you’re a character in an Austen novel, should you marry for love or marry for money?” That question synthesizes the focus on plot and characterization in the early units with the social issues — gender, economics, power — that tend to come up in discussion from the beginning to the end.

The overall structure of the course is derived from the structure of Austen’s novels themselves. Each time we meet, we’ll have read one volume of fiction (so either a third or half of a novel). So really, working backwards from what I want the course and then the unit to accomplish, and in terms of assessment outcomes, I ultimately had to decide how to separate some mini-lessons — based on the questions that typically come up in a sidebar — across three days. Here’s what the unit plan looks like:

Now the fun part: how do I teach the technical terminology about plot and the history of the three-volume novel in an interactive, fun, not-overwhelming way?

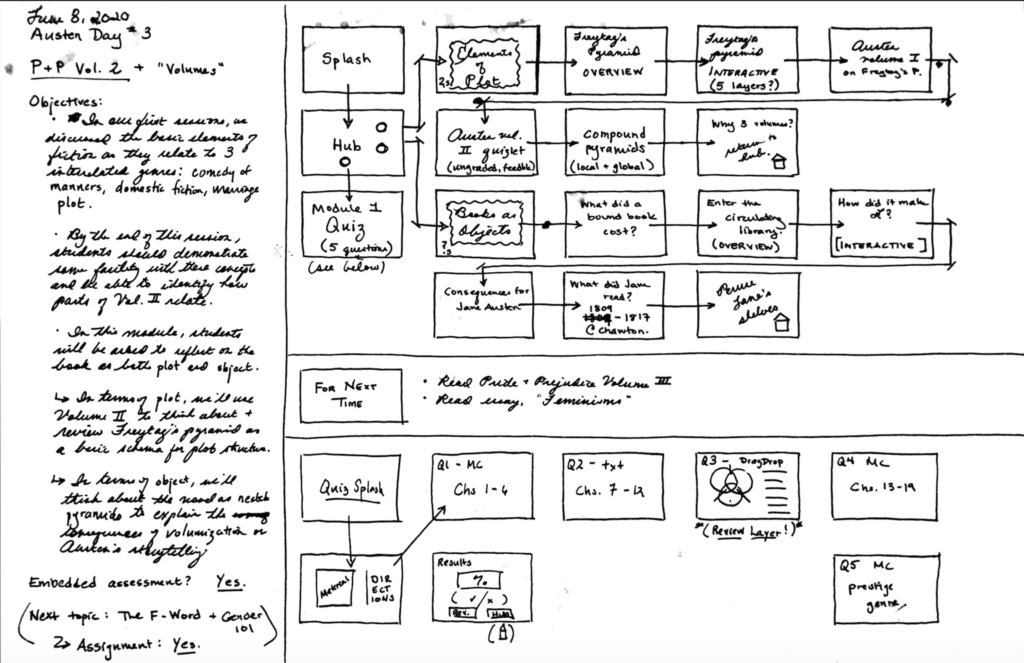

I started by making an ink-and-paper storyboard, listing out some of my learning objectives and thinking about what the design for a “P&P Day 2” module might look like.

First, I decided to separate the two topics I identified into distinct slide paths linked to a central hub. I figured I could explain each topic in about 5-7 minutes, but asking learners to endure both of them in succession seemed tough.

Separating the “Elements of Plot” mini-lesson from the “Books as Objects” mini-lesson allows learners to treat each separately, but sequentially. And in scripting “Elements of Plot,” I end with a question that links the two lessons together while allowing the user to return to the hub.

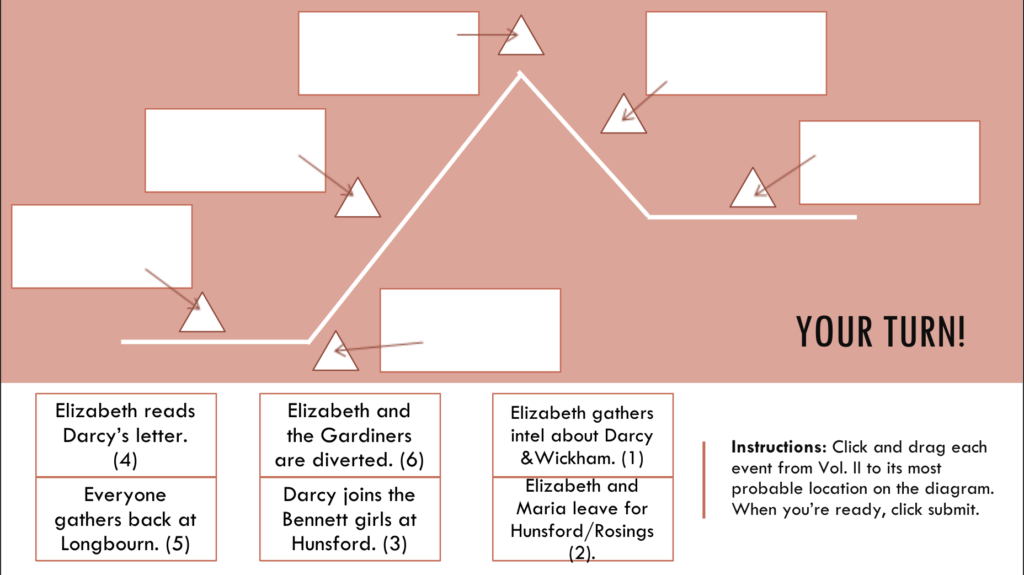

The storyboard itself is pretty simple — no more than story beats. But I did want to make sure that no more than learners encountered no more than two narrated “information” slides before having to do something interactive. It might be as basic as answering a question with an educated guess or playing with a graphic organizer.

I could also include a low-stakes quiz, preventing users from moving forward with the lesson until they demonstrate that they’ve understood the basic concept.

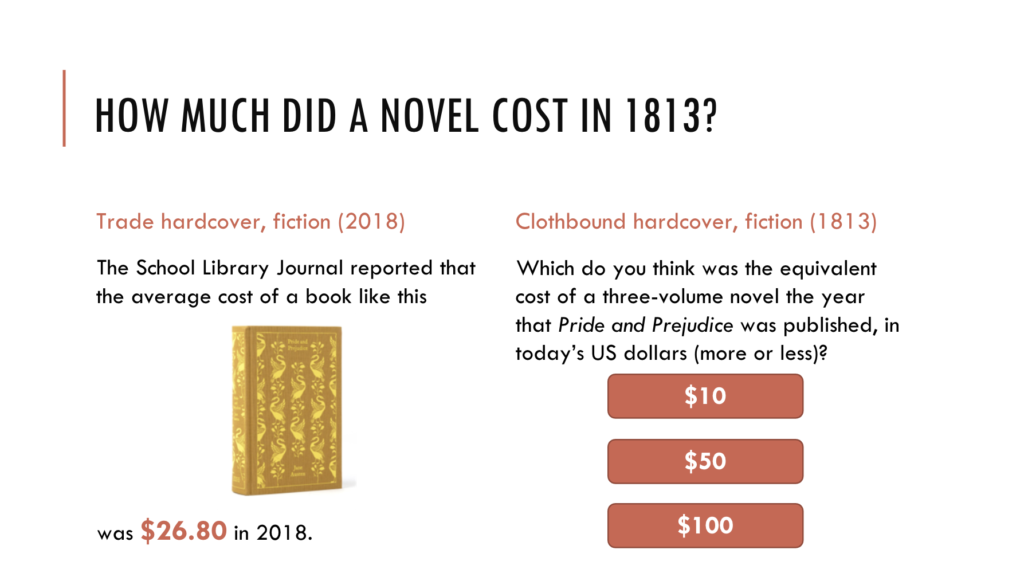

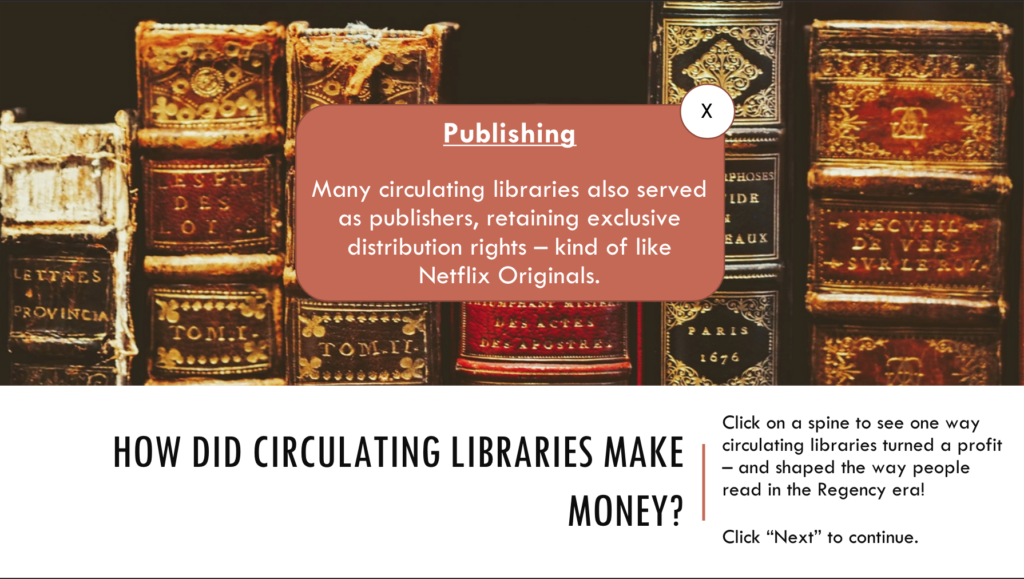

I thought of a more involved, informative interactive to follow an explainer slide about what a “circulating library” was. I thought it might be fun to have learners click different hotspots on antique book spines to learn about a different way that the business made money.

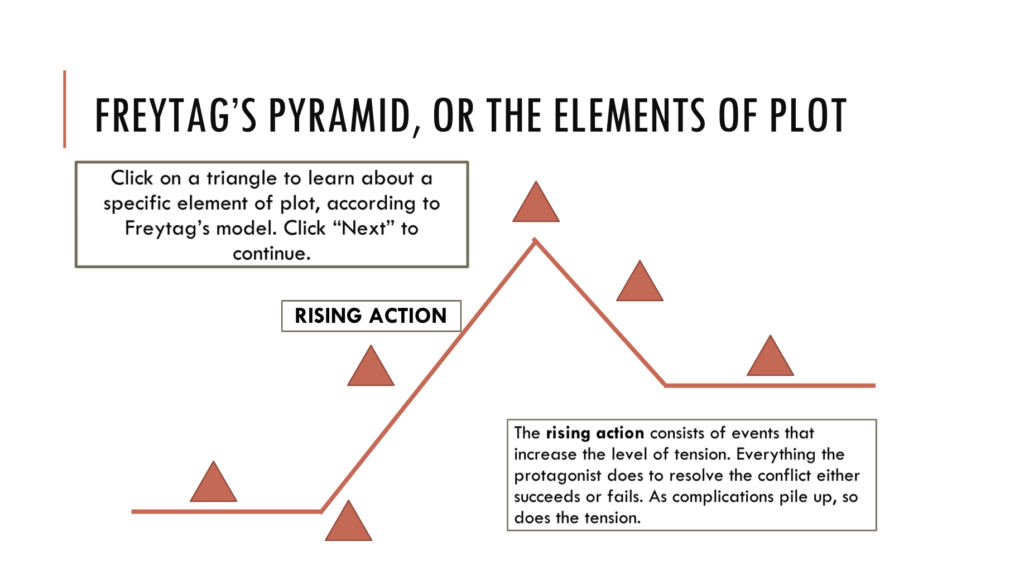

In each of these cases, I wanted to create interactives that offered an experience you probably couldn’t get from a traditional lecture. It’s one thing to draw Freytag’s pyramid on the board and label the parts while everyone copies it down. It’s another to ask students to classify the parts themselves based on the reading they’ve just done. And it’s a VERY different thing to show old books up close and invite users to “touch” them as a way to reveal some information.

The various interactives were the first elements I designed in these mini-lessons, since they’re probably the moments of greatest learner engagement. Keeping myself to a strict slide count around them helped me script only what was essential to setting up those interactions and avoid “nice-to-know” information.

Once I had the script written, I mocked up the slide decks in PowerPoint, using and editing several templates, before importing them into Articulate Storyline to build the interactions and recording/mixing the narration in Audacity.

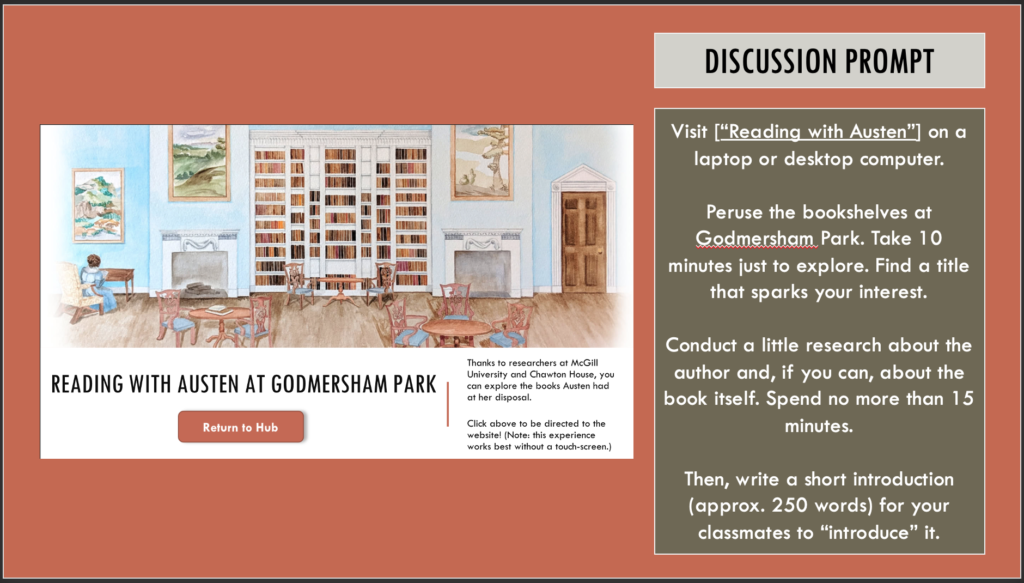

I also ended the “Books as Objects” module with a link to a resource that I want learners to use for a quick writing assignment delivered through Canvas, this university’s learning management system.

Even this discussion post has a larger purpose. It builds off of the question about Austen’s literary world explored in the previous module, and it sets the stage for reading other kinds of literature after the next. It also begins teaching the basic skills needed for a final curatorial assignment at the very end of the class, where students need to present an adaptation of Austen’s work as part of a “gallery.”

Since I want to be able to track learner completion in Canvas LMS, and since I want learners to remember what they have and haven’t done, I set up a simple true/false variable to alter the hub page upon completion of a unit. This was especially important because of the third item on the hub, a check-in quiz meant to simulate the ones I gave face-to-face.

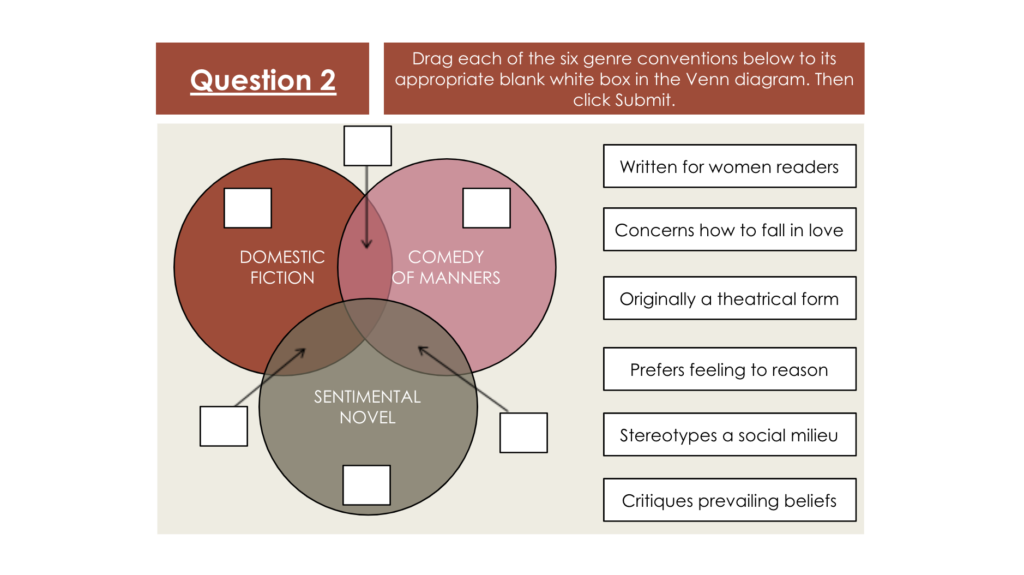

The quiz itself is pretty standard Articulate fare, though I am proud of a little drag and drop Venn diagram I set up to see how comfortable students feel using the terms for different genres. Each question can be submitted up to two times, so there’s some safety to fail. And since each quiz is only worth a couple of points, these really are safe to fail. They’re just “check-ins” that aren’t meant to torpedo learners’ grades.

While I think the design of these slides is pretty solid, I really want to underscore that PowerPoint did the heavy lifting! If I need to produce one module for every volume, that’s already 16 on the docket for this course, plus additional materials for other readings, activities, and assignments. I knew if there was a template I really liked in PowerPoint, it would be much easier to just use a set of master slides and vary the colors by unit.

Establishing a consistent visual language was also important to me at multiple levels, so that learners could know at a glance what kind of thing they’re looking at and whether they’re in “the right place.” Here’s a mockup of the color scheme by slide type for the next unit, on Sense and Sensibility.

Finally, since accessibility is crucial, I used Articulate’s Notes tab to include a complete transcript of my narration. It corresponds to the closed captions available to the learner on every narrated portion of the module. I recognize that a couple of the interactives would benefit from additional narration to make them fully accessible to visually impaired users, and I hope to make those additions during my next recording session.

By blending these modules with asynchronous writing and video activities, my students and I can spend our (more limited) discussion time doing what we really want to do: talking about what we think about the books.